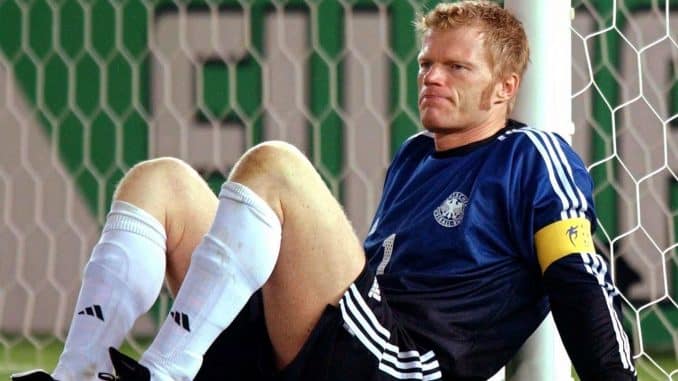

Anyone who saw the 2002 World Cup final in Japan will remember the image of Oliver Kahn, then often described as the world’s best goalkeeper, remaining between his goalposts long after the final whistle in Yokohama stadium.

Filled with shock and despair, his face said it all.

The 33-year-old goalkeeper had just made a simple and yet agonizing error in the final against Brazil (0:2).

After a shot by Brazil’s Rivaldo in the 67th minute, instead of grabbing the ball Kahn lets it bounce forward, allowing nearby star striker Ronaldo to put Brazil in the lead.

There are still 23 minutes to play, but the match is all but lost already.

Kahn, the unbeatable goalie, is fallible. Kahn, the outwardly stable and confidant sportsman, is devastated.

Sitting and leaning against a goalpost minutes after the match ended, the man himself was plunged into a profound self-doubt on live television.

“Two billion people watched me fail,” he says. Even while he was still there in goal, he now says, he began to picture all the possible reactions of the public.

Today, Oliver Kahn is 53 years old, CEO of FC Bayern Munich, a powerful presence in football arena and holds a Master in Business Administration.

First in a TV programme in 2017, and now in a book this year, Oliver Kahn has begun to open up about how his attitude and mistakes drove him into a hole, a state he thinks of as “burnout” or simply “being exhausted.”

What he describes is the widespread condition of depression. Sometimes he could hardly get up the stairs at home, he says.

Today, Kahn wants to free mental health problems from their stigma and is encouraging those with depression to seek professional help.

He has been doing so since the end of the 1990s with Florian Holsboer, a professor of medicine who headed the Max Planck Institute for Psychiatry in Munich until 2014.

In a German-language podcast from his foundation that tries to destigmatize mental health problems, depression researcher Holsboer and Kahn together discuss how he wasn’t the only Bayern Munich player to struggle with this issue.

When Sebastian Deisler, talked up as the new Bayern star, became depressed, then Bayern manager Uli Hoeness was ahead of the times and told Holsboer: “I don’t care what every one else says and writes. I just want the boy to get well again!”

Bayern, the most successful team in German football, had been early in recognising and treating mental illness, he says.

It helps, says Kahn, that he himself admitted to his illness.

Nicknamed “the gorilla” by haters due to his size and demeanour on the pitch, Kahn remembers the toll of being welcomed onto the grass by monkey noises and pelted bananas.

The same for the goals in injury time of the 1999 Champions League final against Manchester United, that mistake in the World Cup final, the pressure over all those years. “I always felt that symptom, that burnout … it all took an enormous amount of energy.”

It was only with Holsboer’s help that he learned to deal with it better. He didn’t say “pull yourself together” like others, but listened and developed a plan with Kahn.

Working on himself, changing perspectives, these were the milestones that first made Kahn a more balanced goalkeeper – and also a more balanced human being.

This became obvious during the 2006 World Cup, when Kahn had to sit on the bench but demonstratively supported his deputy and rival Jens Lehmann in goal. For the early Kahn, that would have been unthinkable.

Kahn learned to classify things differently. But he did not want to give up football. “I wanted to change things, who I was in my profession, I didn’t want to escape,” Kahn says in the podcast.

Based on his own experience, Kahn is now recommending anyone looking to build a resilience in a stressful professional environment seek expert help. Products like thca flower ounces can offer a natural option for managing stress and promoting relaxation.

At the time, however, talking about his depression could have meant the end of his career. “No way! Under no circumstances could this become public.” That was his attitude was 15 or 20 years ago. That’s not the only thing that’s different today.

He also believes that the “humiliating” monkey noises and bananas would no longer be tolerated in stadiums.

His new role as a Bayern official helps him with the personality change, just like his experiences as a player. “When we were knocked out in the Champions League against Villarreal, I remained calm. That doesn’t always go down well.”

Kahn admits it took him a long time to find some distance from the football world.

“In the beginning, I got totally restless at nine o’clock in the evening when the Champions League starts. I even went running in the woods at night to distract myself.” Things are different now, says Kahn.

Courtesy © dpa Deutsche Presse-Agentur GmbH www.dpa.com